Education Across Cultures

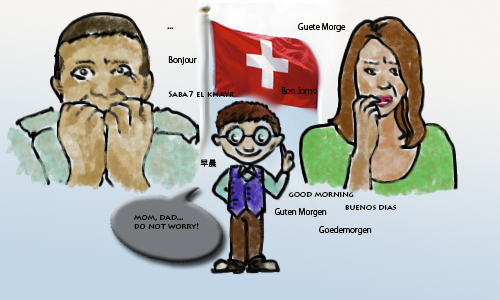

Immersion and consequent cultural integration for our children seems simple: we move abroad and our children can embrace our ‘living abroad project’ by attending a local school and guess what, they will become fluent in a new language, which brings them unique skills and status compared with most kids back home. They are likely to develop enduring dexterity in switching languages, according to the research, which will stand them in good stead for the rest of their lives. They could learn other languages more quickly, and even stave off Alzheimer’s once they are over 50. There are obvious advantages from learning another language. But is it as easy as it seems to adopt a new culture and language, and what is the cost to our family culture(s) and identity?

Cultural integration is difficult to achieve without speaking the local language. Fluency also provides evidence that a child has gained something tangible in compensation for the complications of living abroad. But it cannot compensate for being away from family and long-standing friends or losing one’s ‘roots’ (the importance of this varies according to your family’s previous global mobility). You might also be sacrificing established networks that help children in less tangible ways and, more worryingly, jeopardising their educational success. Is it worth immersing our children? Only if we are prepared to immerse ourselves, the parents, too, or play the role of an inter-cultural translator to help our children hold onto their international culture too.

Moving to Switzerland with an international company used to be a three to five year project and in this timespan parents could be sure of an unforgettable cultural experience as well as a chance to make real local friends while here. International schools ensured the children did not lose out too much from having to move schools a few times in the course of their education. It was not considered realistic to learn a new language fluently without losing one’s own culture or language.

However, nowadays more families are willing to throw their culture into the global pot. Indeed, the world seems smaller. Cultural imperialism is out, cultural relativity is in. Why should my child grow up harking back to a previous national identity that seems barely relevant to global nomads? Schools also seem comparable despite the language differences. And when families stay longer than five years, those with two or more children have to face the fact that that their children’s entire education might be in Switzerland, which results in quite a different perspective on their futures.

There are many cultural dimensions to ‘going local’ and those who marry into a Swiss family are likely to have the greatest understanding of intercultural differences. Although speaking local Swiss German in this part of Switzerland is essential for any real integration, learning this dialect does not hold all the answers for children’s future prospects if they do not speak standard German and understand the difference, as many English-speaking parents are discovering years after going down the local route. Standard written German is quite different to local German and in Zurich children do not embark on the official school language until they have left kindergarten at six or seven. However, they might already need, by the age of eight, to be showing talent and some capability to read and write in standard German – a version of the language that even their Swiss friends find strange. This is because many local teachers are already mentally dividing children in Zurich state schools into ‘academic’ and ‘vocational’ groups for 4th to 6th class (leading to the Gymipruefung, the test to enter academic secondary schools: Gymnasium).

In my own son’s case, he did not get a place in an international school so he attended a local school for three years. Once he was fluent in Swiss German his English at home did become a little accented but, more importantly, he started to see himself as incapable of learning in English despite being an enthusiastic reader of English books. One day he brought home from school a comment about foreigners in Zurich and I wondered if I had sent him backwards culturally by giving him more linguistic advantages. In mono-linguistic but multicultural London there was widespread discussion about tolerance of difference and how to ensure anti-discriminatory practice which I found entirely lacking in our local Swiss state school.

Cultural differences abound just below the surface of what children can discuss at home, so here are my key tips for helping your children adjust to living in two or more cultures, or moving between them regularly:

1. Talk about the tangible differences you can observe in the street in the new and old place.

When you are walking down the road, notice the colour and meaning of road signs, which way the traffic lights change, what sound barriers look like on the motorway, what public transport is like, what people hang in their windows. Next time you are home or looking at books from home, compare how these things look here and there. Your children will become observant and able to link differences with what they show about people in different places.

2. Identify cultural and linguistic differences and share them with your child.

Youngest child…

For example, when people greet each other they shake hands here, when they say ‘cheers’ they use each other’s name, in England flats do not share a laundry room, at your grandparents’ house they put all their recycling in a big bin and do not tie it in a bundle….

Middle school age…

In German ‘bank’ is a bench and a place to put your money, in English it is for money and a ‘bank of sand’ is a pile along the edge of a road or shore.

Older children…

In Switzerland the country is governed by a multi-party committee, and the leader can be from any party, whereas back in the U.S. we have two main parties and only one can hold the presidency.

3. Make a family tree showing the cultures and places of birth as well as year of birth. Show it to your friends and neighbours who could share their many cultures with you too.

4. Clarify what is a helpful generalisation that enables us to think what characterises a particular society, versus an unhelpful cultural stereotype that limits our thinking.

For example, Switzerland is famous for its clean streets and punctual public transport which are generally verifiable. The rural Swiss are not just simple farmers, this is a stereotype. Britain is a historic and traditional place but the British are not necessarily conventional or old-fashioned. America is the land of the automobile where the car industry started, but Americans do not all espouse car driving instead of public transport and many do not own a car.

5. Notice cultural differences in teaching styles and systems: if your child attends a Swiss or bilingual school (many bilingual schools are majority Swiss) this can help them to feel you understand and respect their experience of straddling different worlds.

Parents’ comment: “The Germanic system seemed to motivate by endless testing, but without that my son lacked any real desire to succeed. I told him at an English-speaking secondary school the teachers might be nicer but he would have to work out of respect for us paying his fees and at a Swiss school he would have more tests and stricter discipline at school.”

One problem we all have identifying cultural differences between teachers and schools, and articulating them with any confidence, is caused by the fact that we only see one or two schools, preventing us from developing a broad view of Swiss education. Keep talking to friends, tapping into forums online and exchanging information to get the most out of your years in Switzerland. And don’t forget, no matter how much research we do and how much care we take, a certain amount of what happens in the future is simply unknowable. It helps in the moments when the wonderful cultural experience we have given our children feels like a cultural minefield.

By Monica Shah

Monica is Head of Children First, an international nonprofit nursery school in Zurich.

Illustration by Susana Gutierrez

Susana is a mother of two little girls who moved to Zurich four years ago, during the maternity leave of her first daughter. She is originally from Spain but lived in London for almost 10 years. She has a very eclectic career from acting to Law, to IT project management. Drawing however has always been a permanent hobby of hers.

Resources:

Monica Reppas-Schmid, Living Cultures

SIETAR, Society for Intercultural Education Training and Research

Global People Transitions. Angela Weinberger: coaching, transitions

Join the Families in Zurich Yahoo! group moderated by Carmen Crenshaw-Hovey

Tours of Zurich in English by Bill Hovey, History teacher at ZIS (Zurich International School)